Analyzing Benchmark

pt. 1

Hi,

Welcome to Roll Call, a newsletter about the state of policy and technology in public safety, and the people shaping it. If you’d like to sign up, you can do so here. Or just read on…

TL;DR

Benchmark is in a precarious position: bolted on top of other major data sources that it depends on, but solving an important problem with a massive and misunderstood market.

A Hidden TAM: total addressable market is much larger than you’d think because so many dollars are hidden in liability costs that agencies already pay.

Differences between machine learning and regression-based early intervention systems are overblown today. Future success and a deep moat depends on Benchmark proving that gains from their methods will increase over time and aren’t easily copied by other providers.

In the ShotSpotter piece, I said I would be making these analyses for paid subscribers only. I changed my mind. Because the landscape in public safety technology is so dynamic, the companies we look at will be worth understanding fully at multiple moments in time. A detailed analysis is only a snapshot, useful in providing context for later developments. The first look at each of these companies will be on the free tier, but paid subscribers will receive short updates as company strategies change or market shifts impact how they approach public safety. As an example, I am hoping to talk to the ShotSpotter exec team in the near future about some of the topics raised in my piece. Here’s the CEO of ShotSpotter responding to my thinking out loud about ShotSpotter’s place in the gunshot detection policy/tech ecosystem:

Today’s note is on Benchmark Analytics. Benchmark is a young company (founded in 2016) that has quickly developed a reputation as a data-driven, potent software solution to the issue of police misconduct. I was curious if Benchmark’s positioning was measurably stronger than competitors in this space, and who is most likely to target them as an acquisition in the next year (per my predictions). This was a thornier process than ShotSpotter because the company is much smaller and has far less data to look at, the policy questions are trickier, and it’s deeply interwoven with tort law and insurance dynamics. Be warned, we’re going to jump into a bit of rabbit hole regarding municipal risk management and law enforcement liability. Skip if you must, but I think the context is worth the investment.

Here we go:

The Benchmark Thesis

Short version: We believe that we can repair community trust and reduce lawsuits against police by identifying risk-prone officers before they get off track.

Long version: Community trust (the number two most important narrative in policing, according to IACP training sessions) erodes when sworn officers take actions that neighbors consider unjustified. There are three layers to the harm caused by police misconduct. First, misconduct stretches the empathetic distance between the community and the agency. The distance makes it difficult for an agency to recruit, to communicate effectively to the community, and to be proactive in areas that require buy-in from the public. Second, the agency or municipality must pay out significant amounts of money in lawsuits to complainants, which can have a dramatic effect on operations. The other side of the same coin is the third layer, which is that this is taxpayer money. We foot the bill when public safety agencies, committed to protecting us, harm us. At a community level, this is self-inflicted pain: money raised by neighbors being paid out to affected, injured, and in the worst cases, grieving, neighbors.

I’ve been watching a lot of Cells at Work on Netflix, so forgive the metaphor - police misconduct is a lot like an autoimmune disease, where the body’s immune system (police) fails to differentiate between harmful invaders (some viruses, bacteria, and crime) and native, important cells (neighbors). In type 1 diabetes, for example, one kind of white blood cell called T lymphocytes targets insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, believing them to be dangerous. Reader, beta cells are not dangerous. Overreacting to these cells disables our ability to manage blood glucose levels, which causes a host of health issues that require speedy intervention or we can die.

Stretching the metaphor to the breaking point now, Benchmark Analytics and other early intervention systems (EIS) are autoimmune suppressants. Benchmark believes they have the best medici- err, software to identify actors that increase the riskiness of incidents with neighbors. Then Benchmark adds several personnel management tools that aim to align the company with the goals of high-performing officers in their training and career development.

Benchmark Analytics’ mission, in their own words:

“To transform police force management through an all-in-one police force management system and early intervention software platform that provides a 360° holistic view of every officer - in police departments of every size.”

How Big is the Problem?

Benchmark Analytics helps municipalities and public safety agencies address police misconduct. As noted above, the harm caused by misconduct is difficult to measure completely, as the effect is felt on qualitative and quantitative facets. We can’t nail down the exact amount of trust lost, but you could reasonably argue the that price paid is equal to the cost of every bodyworn camera program in public safety.

Quantitatively, we can do a little better. The questions we’re working towards here are:

How much does police misconduct cost agencies and municipalities?

Who pays?

Public safety software companies commonly charge some dollar amount per officer per month. For parity, let’s treat civil suit settlements (yikes) as a product. Taking a basket of 10 large, geographically diverse cities, and looking at multiple year periods, we can build this:

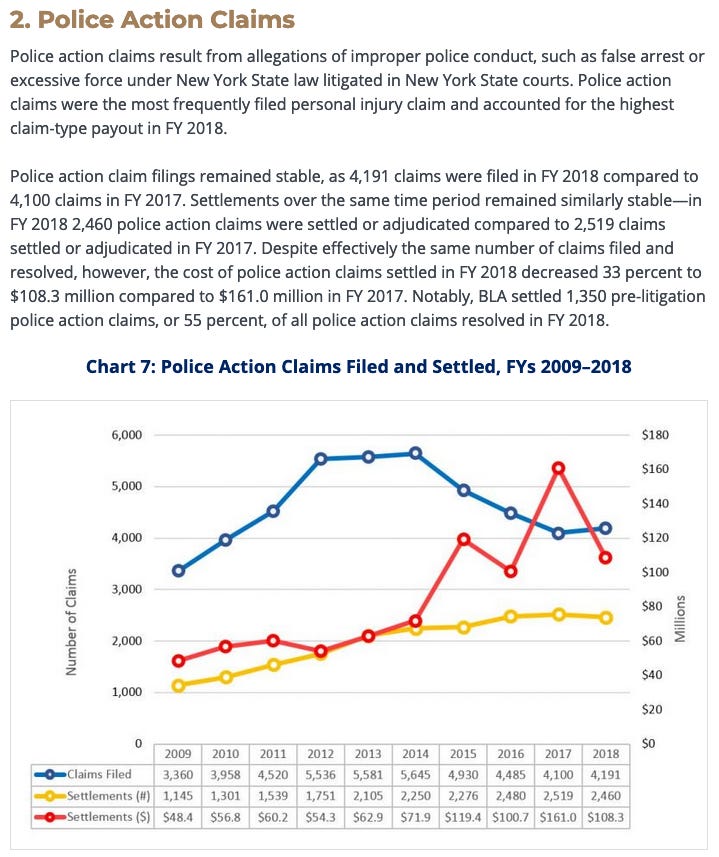

This data is from 2015, so I don’t blame you if you want to see more recent numbers. In 2018 alone, Chicago paid $113M in settlements ($788/mo/officer), and New York paid $108M ($248/mo/officer). More NYPD figures below:

“A small number of New York Police Department (NYPD) claims disproportionately accounted for the total dollar amount paid out on NYPD claims in FY 2018.”

“In FY 2018, five wrongful conviction claims, representing less than one percent of the 3,745 NYPD tort claims resolved during FY 2018, settled for a total of $33.3 million, which accounted for 14% of the total $229.8 million in NYPD payouts.”

We learn two things from this. First, these civil lawsuits follow a Pareto distribution, where a small number of serious cases make up an outsized percentage of total settlement dollars. This is good news, because it means that even addressing just the most egregious police misconduct incidents, skimming off the top, Benchmark can save communities from significant harm - and therefore, the most expensive settlements. Second, civil lawsuits are expensive. Like, very expensive. The per user per month numbers we outlined are similar to large tech initiatives like outfitting a department with bodyworn cameras or building a real-time crime center. There’s significant value to be captured by a company that can minimize litigable action. Let’s get into how the finances are structured, and why.

Looking at who pays through the $$$ lens reveals a muscle in public safety that I wasn’t aware of before: insurance. Big cities, like those listed above, are large enough to self-insure, to plan for some amount of settlements every year. At least, that is what is expected of them. Chicago has underallocated budget for misconduct settlements every year for over a decade. In 2018, costs were underestimated by 500%! The shortfalls required ad hoc bond issuances, which burden taxpayers even further with interest over time.

Small cities don’t have the luxury of deep pockets or hot-potato bond issuances, and need to procure liability insurance. They can choose to individually find private insurance, or join a municipal risk pool - a non-profit joint org that charges premiums, handles cases, and returns dividends if premiums were higher than needed to pay settlements. Two good examples of risk pools are Washington Cities Insurance Authority (158 cities, $36M in 2018 claims) and Arizona Municipal Risk Retention Pool (75 cities). Important to note that risk pools cover all liabilities of cities, police misconduct being only one part - usually the largest part, but only a sector.

Having coverage doesn’t mean small cities are protected from the consequences of serious misconduct incidents, like what happened to Lakewood (WA). In 2018, “a jury returned a $15 million verdict for the death of Leonard Thomas, who was unarmed when a police sniper shot him. While Lakewood's insurance is expected to cover a portion of that payout, the city still has to spend $6.5 million on punitive damages - an amount equivalent to 18% of the city's annual spending.” This kind of event cripples small agencies. If the insurance provider elects to stop covering a city, any lawsuit could bankrupt them. Exposed to unlimited liability, an agency will often disband and the city will contract law enforcement through a neighboring city or county agency.

The insurer has significant leverage over a public safety agency, then. If an insurer can shutter a police department, can they suggest policy changes that would positively affect an agency’s riskiness? This is a surprisingly recent academic debate. The argument put forward in this 2017 paper is that private insurers have an unheralded power to regulate police activities. They can and have influenced cities “to adopt or amend written departmental policies on subjects like the use of force and strip searches, to change the way they train their officers, and even to fire problem officers from the beat up to the chief.” The paper does a great job of laying out the scope of the question, and I encourage reading the whole thing. But for our questions, the weight of this insurer power rests on the extent to which agencies are on the hook for the liability costs they incur.

Now we can answer who pays. Two parts to this question, both addressed in this paper:

How are litigation costs budgeted? How accountable are agencies to lawsuit costs?

Large agencies tend to have budget allocated for settlement costs, where smaller agencies are more likely to have insurance premiums handled by the city through central funds or risk pools.

What impact does that have on agencies? Do they feel the effects of those costs?

“Having agencies pay money out of their budgets toward settlements and judgments does not necessarily impose a financial burden on those agencies. Some law enforcement agencies pay millions of dollars from their budgets for settlements and judgments yet feel no financial consequences of these payments because they receive money during the budgeting process for litigation payouts , overages are paid from central funds, and litigation savings are not enjoyed by the agencies.”

In large agencies, almost all PDs feel no financial impact, and nearly 70% of law enforcement by sworn officer count feels no financial impact from settlement costs.

To wrap this section, the takeaways are that the costs of police liability suits are high, multiple parties have a vested interest in reducing police misconduct, and a few of those have outsized leverage not usually factored into how we traditionally think of law enforcement operations.

Strategic Model

Thinking about Benchmark’s place on the modern duty belt, take a look at the diagram above. To put it in human infrastructure terms, Benchmark builds a specific type of memory and enhances intuition: ‘bad-apple’ detection and prediction as a problem-solving skill. The product suite is entirely post-incident, which allows it to specialize in a few important, detailed functions, but also means that it is not the point of truth for the data that populates its software. Records from calls for service and incident reports need to be clean, trustworthy, and structured for a predictive software tool to have the desired effect.

Putting that aside, let’s look at what Benchmark Analytics does with the data it has. The full suite pulls together data from the agency’s CAD, RMS, personnel management system, and - if they have one - Internal Affairs products. Combining this data paints a “holistic” (Benchmark’s words) picture of how risky an officer is. Detecting risk is one thing; it’s then the supervisors’ duty to intervene, build a plan to get officers on track, and help them execute against those goals using other Benchmark tools.

Products

It’s important to note that Benchmark’s product suite is valuable because of how its disparate parts work together, not because any of them are valuable on their own. You could argue First Sign is the most valuable piece, but it’s nothing without the data feeding it. There’s three products that make up what what’s called the Benchmark Blueprint:

Benchmark Management System: The foundation for everything else. Integrates (free of charge) with an agency’s CAD and RMS, and for some agencies can serve as the personnel management system and internal affairs tool.

Value Prop: Mixed, for two reasons. First, it’s worth saying again that Benchmark’s data is downstream from incidents, forcing the company to trust a lot of outsiders (users entering data, third party software cos, etc.) that can impact the power of their analytics. Second, analytics software is usually bolted onto workflow-oriented software, which makes it difficult to displace bigger vendors. BMS will never replace a CAD or RMS. Even the areas where BMS could make a claim that it is superior to what’s out there, it sometimes doesn’t check all the boxes. BMS does not replace a full enterprise personnel management sytem, which would require scheduling, payscales, benefits, and a host of human resources capabilities. BMS sometimes does not even replace internal affairs software. In at least one contract, Benchmark was procured as a supplement to IAPro, with the expectation that the two would integrate.

Complexity: Minimal. Once interfaces have been developed across the most common vendors that Benchmark needs to talk to, most of complexity is handled.

First Sign Early Intervention: The claim to fame for Benchmark. A preventative system that uses the BMS data to give supervisors and administrators the ability to address and correct problematic behavior before an adverse event occurs. Below is a list of the factors that First Sign uses to flag individuals.

Value Prop: Valuable as a supervisory tool, if improvements over today’s standards can continue into the future. The biggest limiting factor in current early intervention systems is that there are too many false positives, and too many false negatives. Benchmark claims that competing trigger-based systems have a 71% false positive and a 89% false negative rate (in another post, they claim its 78% false pos and 90% false neg, but let’s interpret generously). If that’s true, most EIS’s are essentially useless! The paper they cite, however, does not back that up.

The false positive rate in the simple pre-existing system at Charlotte-Mecklenburg PD was 44%, and false negative rate was 48%. That’s still annoying and doesn’t inspire trust in the tool, but it’s certainly not useless. The same paper also outlines in detail the machine learning methods that Benchmark has adopted, and the performance gains compared to a simple, trigger-based system. The new, Benchmark-esque system had a false positive rate of 30% and a false negative rate of 42%, with raw improvements noted in the table. The problem of police misconduct is worth spending on, but how much is a 1% decrease in false positive/negative rate worth?

Further, is that improvement sustainable? I believe the answer here is yes - Benchmark has partnered with the University of Chicago and the Joyce Foundation in a research consortium, which, coupled with the commitment to machine learning and leveraging users’ data to continuously train the model, seems like a path to further gains.

Complexity: Little. The tool is designed to - and succeeds at - making the subjective objective. First Sign makes a complicated decision legible.

Case Action Response Engine (CARE): Guidance for action to take after First Sign.

Value Prop: Holds the hand of supervisors through the intervention process.

Complexity: None.

Competitive Landscape

Valor Equity Partners - A private equity firm invested in ~30 companies across a range of markets, focused mostly on strong founding teams. Unclear what the position size in Benchmark is.

IAPro (CI Technologies) - CI Technologies is the parent company for the internal affairs category leader IAPro/BlueTeam and early intervention system EIPro. The company is established (since 1992) and exclusively focused on public safety, and because the niche is small and internal affairs investigations data has to be maintained separately from a criminal records management system, the company has been naturally protected from the big RMS players coming onto their turf, until recently. CI Tech has 800+ customers globally, and most of the major cities in the United States.

Guardian Tracking - Guardian heavily leans into messaging that positions them as the best tool for building a positive workplace culture, supporting/retaining employees, and recognizing productive behavior. Started in 2007, it’s a team of 10 employees that has amassed a client list of 1,100+ organizations quickly. Pricing, per their calculator, is roughly 25% what Benchmark Analytics charges, using Nashville Metro PD’s contract and sworn count as representative.

Second Order Competition

Learning Management Systems - Lexipol and PowerDMS are educational and compliance tools. Agencies use them partially to shield themselves from liabilities associated with having under-trained or under-informed officers. Lexipol especially brands itself as a liability shield.

Big RMS Providers - The more valuable the insight, the more likely it is that the point-of-truth data providers decide to move in and provide the insights themselves. Axon would be included here, as they just released their Standards module in Cincinnati, but the records solution is not widely adopted enough to be as big a threat as the providers pictured.

Business Model

Subscription-based SaaS revenue, with deployment costs spread over contract. Past initial contract, option years escalate in cost. Nashville Metro PD contract is the best example.

$5.22 per officer per month ($91,000 per year)

A sum of $455,000 over first 5 years

Risks

Do agencies embrace a software solution whose main value is identifying low-performing employees? Will they accept it as a full personnel solution?

The tool itself is not complex, and the model is spelled out clearly in academic work. Can Benchmark improve it over time to increase the lead they have?

Key Metrics

TAM - The total cost of police misconduct liability suits, plus whatever Benchmark can pull off of traditional RMS and LMS systems with personnel/training management. If I spent another 3 days on it, I could build a strong case for a specific number, but I’ll estimate the average per officer per month cost of settlements to be $55 dollars, which means the most immediately addressable TAM is $660M. The most amazing thing about the TAM is that it’s already being paid!

Key Players

Almost all of the key people at Benchmark have worked together, following CEO Ron Huberman across various Chicago bureaucracies: Chicago PD, Mayor Daley’s staff, Chicago Transit Authority, and/or Chicago Public Schools. After leaving municipal government, Huberman founded TeacherMatch, which was sold to PeopleAdmin in 2016.

The TeacherMatch Mafia includes:

Ron Huberman - CEO (LinkedIn)

Sarah Kremsner - COO (LinkedIn)

Bob Tulini - CMO (LinkedIn)

Nick Montgomery - Chief Research Officer (LinkedIn)

7 Open Roles (Public)

7 open roles on ~32 current employees… That’s an immediate 22% increase in team size. Aggressive, and befitting a growth-equity-backed tech co.

Data (Data Scientist, Data Pipeline Analyst)

People Ops (Director of Recruiting)

Pro Services (Implementation Lead, Configuration Specialist, Product Integration Specialist)

Sales (Market Development Rep)

Other Reference Docs

How Governments Pay by Joanna C Schwartz

Material I wanted to read but couldn’t:

Cost of Police Misconduct Cases Soars in Big U.S. Cities (WSJ, 2015) by Zusha Elinson and Dan Frosch

best I could do was this article summarizing the WSJ piece

Thanks for reading. Send me feedback at mitchell@rollcall.media! If you enjoy this newsletter, please share it, forward it to your friends, or just sign up here.

-MA

Recommended Reading

Surveillance CCTV by Michael Kwet

New Trophies of Domesticity by Amanda Mull

On the Ground with Lis Smith, the Political Pro who Invented Mayor Pete by Clare Malone

Ben Evans - Tech in 2020 Presentation (regulation and tech! we outchea!)