Hi,

Welcome to Roll Call, a newsletter about the state of policy and technology in public safety, and the people shaping it. If you’d like to sign up, you can do so here. Or just read on…

Judge Dredd: “It’s a lie! The evidence has been falsified. It’s impossible! I never broke the law! I am the Law!”

Everyone has heard of the long arm of the law. Today I’m writing about the strong arm of the law. Judge Dredd is just one man, and so is limited in how far his form of justice can reach. However, as a Street Judge empowered to convict, sentence, and execute offenders, the strength concentrated in just-one-man Dredd is extraordinary. And dangerous. All arms are not created equal when writing or enforcing the law. This essay is an introduction to the distribution and concentration of power in a police department.

Power is fundamental in understanding the topics that Roll Call explores. The law only matters when it’s enforced. Technology companies influence the way officers interact with neighbors simply by putting their products on duty belts. Unelected officials often drive procurement decisions, union leaders craft discipline policy, and local media can show - or hide - the inner workings of an agency. Power is the current running through municipal circuits, connecting people, policies, and technologies. This feels important to write about now because of two stories: a story from the community where I live, and a story from the company that I worked at. After, we’ll introduce the framework of power in a police department.

Phoenix Police, A Near Miss, and Aftermath

I live in Phoenix, Arizona. It is one of the fastest growing cities in the country, for a bunch of reasons: it has cheaper land and lower housing costs than other massive metros, there’s a well-educated workforce, it has unmatched Mexican food, and it’s so hot you want to die. It’s wonderful. The growth hasn’t always been smooth, however. The city and Phoenix PD have gone through the ringer over the last 15 years, dealing with drought, the recession, the subsequent hiring freeze, all on top of wild population growth. The police department has also had to cope with the same cultural struggles as most other law enforcement agencies in the country after the events of Ferguson. Just when it felt like Phoenix PD had made up ground and hit its stride from a staffing and funding standpoint, there was the liminal moment of this summer.

Without restating the entire case, a young black family was shopping at a Family Dollar store, where it is alleged that the 4-year old daughter shoplifted a doll without her parents’ knowledge. It has since come out that the adult male also stole items. An officer present from a separate shoplifting call was alerted and told the parents to stop as they were pulling out of the parking lot. The adults ignored the command. Officers followed the car (without lights or sirens) a short distance to the apartment complex of the family’s babysitter. The situation then escalated. They approached the vehicle with sidearms drawn, violently forced the parents out of the car, removed the other child present - a 1-year old infant - from the mother’s arms, and used strong language like “I’m going to shoot you in your f---ing face,” and “I could have shot you in front of your f---ing kids.”

It was a near miss, and poor handling of a messy situation. It ignited something in the city, whose residents had become uncomfortably accustomed to leading national police shooting statistics. The intent here is not to pile onto Phoenix PD or to exculpate the suspects, but to give context for what came next. In the aftermath of the near-shooting, some great local reporting dug into oversight policy for Phoenix PD. The whole piece is worth reading, but here’s the money section:

“That's because ... hundreds of ... Phoenix police officers in recent years were allowed to erase records of their misconduct from files kept by the Police Department.

The practice, which the Department refers to as ‘purging,’ has been standard for more than two decades under the police union's contract, but the public has been unaware of it.

The contract also prohibits misconduct detailed in the purged records from being considered in future disciplinary investigations or performance evaluations.”

The PLEA union contract allows for minor misconduct records to be purged after 3 years, and misconduct that leads to a suspension after 5 years. However, there are so many exceptions that the unwritten policy, it seems, is that records can be purged in less than a year. Those records then aren’t available for annual performance reviews, for transfers, or for promotions. “Well,” you might be thinking, “maybe this is a little-known trick that only the most crafty officers are able to pull off?” Unfortunately, that is not the case: 90% of sustained misconduct records had been purged.

This is an incredible amount of power! Illuminated by this example, for me, was that the police union had co-opted part of the disciplinary process - and they’d used existing record retention policy at the state level as support for doing so. Are no other disciplinary practices designed for incomplete information? Are no internal policies enforced differently than others? Is Phoenix PD the only one? Possible, yes; feasible, no. Again, if you’ll forgive an architecture metaphor, this story helps us understand the rebar in the public safety concrete. We are not calling for either ripping it out wholesale or adding additional support, but for understanding where it is and what actions it supports.

Technology and Discretion

I worked at Axon, formerly Taser, for two years. In late 2016, I was asked one of the most genuine and impactful interview questions I’ve been on the receiving end of. “We sell bodyworn cameras and Tasers to police. Law enforcement is essentially our entire customer base. At the same time, there are nascent activist movements calling for significant reforms in the way agencies operate. What responsibility do we have… I guess I’m asking how should we, as a company, balance these different pressures on us?” This was a seasoned product marketing manager asking how I, a senior in college, thought a public company should position itself with words and actions to help communities across the country address a crisis both national and hyper-local. I was hooked. I believe I answered with something hokey in line with Axon’s mission statements - Protect Truth, Protect Life - and said that especially on the bodyworn camera side of the equation, Axon had to engage in good faith with community questions about the truth of officers’ statements and take a more active role in determining truth.

Right away, I hope you see where this is going. Over time I realized that there is a tremendous amount of power in creating the tools, but there is far more power in shaping the processes by which they are used. Agencies own the video data. Axon does not actively determine truth. It is not Axon’s prerogative to write agency policies regarding if, how, and when to release video of incidents. It not Axon’s prerogative to write internal memos that dictate when to deploy Tasers. It is Axon’s job to add tools to the modern duty belt, to toss them over the wall from the private sector to the public. It is Axon’s sole prerogative to build products that help sworn law enforcement personnel do their jobs safer and better.

“We shape our tools and, thereafter, our tools shape us.”

- John Culkin and/or Marshall McLuhan

In an ideal world, the tools are deployed in a way that increases trust and accountability within respective communities, but that is outside Axon’s scope. The interesting thing here is that technology companies have an unaccounted for power in building the means by which modern policing is done. On balance, this is neutral power. It can be a good thing - I’d argue that Tasers, for example, are a net good for society - but the good is modulated by the control other actors have over legislation, policy, and oversight. A non-lethal alternative to a sidearm, for example, can become a pain compliance tool that does significant harm to a neighbor if use policies aren’t clearly outlined and enforced. As much power as tech companies have, the executive function of using and monitoring proper use of these tools is stronger. In public safety, there are many of these important trade-offs. There are often no easy answers. We need to work with clear eyes and full hearts to understand and find a balance that neighbors can live with.

The Players

A preface: the law enforcement landscape is complicated. Cities are dynamic and messy. Every municipality will tell you “we do things differently here,” which can’t possibly be true but still somehow is. There are a myriad of factors that change monthly - or faster - that shift power credits and debits. That said, it’ll be fun to explore this and to paint a cubist representation of what’s happening in cities. Treat what follows like a wild over-simplification. Eventually, we’ll outline specific cities in detail, to move out of crude cubist symbolism into something a little more objective. I’m a young Picasso, is what I’m trying to say.

Let’s start with the police department itself, pictured above. We’ve got the Chief of Police nominally at the top of the hierarchy, with command staff (sergeants, lieutenants, captains, etc.) as mid-level management, and sworn officers as line level employees. Think of arrows in this context as vectors of accountability and allegiance, with thickness indicating strength of connection. Sworn officers are accountable to command staff for their job performance. They also are aligned with and reliant upon the police union to negotiate on their behalf. Because a chief is appointed at the city level, it matters that she has the cultural support of sworn officers, but she also maintains control over their assignments, organization structure, and some disciplinary functions.

Zooming out to include city officials: as the cookie cutter example city, we’re looking at a council-manager form of government. This means that a mayor is elected at-large, but functions mainly as the cultural figurehead and an equal member of the legislative city council. The juice is squeezed by the city manager. She operates as the CEO of the city and appoints all department heads, which is why the vectors from the Chief and City Prosecutor are so bold. Hiring and firing power are highly concentrated in the city manager. If, however, a mayor were to run for office and be elected on the promise that he wanted to fire the incumbent chief, that would be something that the city manager would weigh heavily. Lastly, crime doesn’t respect municipal lines. The county sheriff’s office and neighboring police departments work together on operations or mutual aid, and often share resources like an Emergency Communication Center or other large infrastructure projects for cost savings.

Finally, we plug in actors that are further from the action. The Secretary of State and District Attorney provide legal frameworks and bounds on internal policies and workflows. For example, if the Dallas DA says his office won’t prosecute “low-level” crimes like petty theft, that impacts PD operations. The media and voters provide some accountability, but are too removed from the executive branch to have a great deal of influence. I’d argue that the voters’ role in how policing is done is overrated. On the other hand, technology companies are massively underrated. Some firms have an opportunity to change the way officers engage with neighbors without having to get involved in municipal struggles. I’ll quickly argue that there are two players in this network that have a form of entropic power.

The picture above is from the book Deep Simplicity by John Gribbin, which I recommend. A high entropy system is stable. It is low energy and resting in an attractor state. We know that the ball on the left will roll down the cup and eventually come to rest where it is on the right. Based on where the ball is in the picture on the right, we have no idea where the ball started. All start positions lead to the high entropy attractor state. That’s a decent metaphor for the closed political system we’ve outlined above. Unless you are a historian of law enforcement mechanisms, it does not matter how we reached our current system other than to say that it seems very high entropy and unlikely to change. However, tech companies and very popular elected officials are sometimes able to shake the bowl and move the ball off the bottom of the cup, reducing the entropy of the system. They are external inputs injected into the public safety system. These are the only two entities that I’ve seen reliably - but infrequently - reduce entropy in this system. Other legislative or policy driven actors may change the bowl shape a bit, but it requires the public mandate of a electoral candidate or the addition of new technology to actually move the ball. Once the ball is moving again, policy changes can slow down the increase in entropy to allow more time for change. Thank you for indulging this quick physics analogy.

The Muscles of the Law

If the arrows connecting the nodes confused you, that’s alright. They confused me, too. With that many players in the game, accountability wasn’t cutting it to understand the weight of power in certain relationships. There were multiple levers that these actors could pull, sometimes even with the same counterpart. For example, a police chief could make legislative concessions at the city council level in exchange for more budget, which she could then spend on creating a bike cop unit outfitted with bodyworn cameras. Of course, she’ll also have to write new policies that govern their use, and communicate the program to the public to assuage any unfounded fears of surveillance. Just in this example, our chief navigates within multiple streams of power, and has no decision-making power in several.

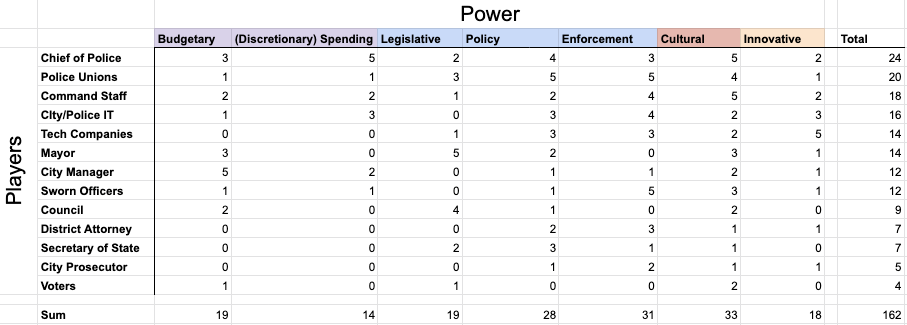

Now we’re starting to flesh out what those arrows connecting the players above mean. Each arrow is made up of several muscles. Can we use some actual (albeit subjective) data to support how the vectors are drawn? Below is my first draft at identifying the muscles of power in a police department. Each cell ranges from 0-5.

Budgetary - The power to sit at the table and negotiate for departmental budget. This includes change to personnel, which moves the floor of the budget, and additional budget for contractual services and equipment.

Discretionary Spending - The power to spend dollars that aren’t already assigned to personnel salary and benefits. The ability to write checks of a certain size without oversight.

Legislative - The power to write and enact the law at a state, city, or county level.

Policy - The power to write operations manuals and internal policies within the agency.

Enforcement - The power to enforce or execute those laws and policies.

Cultural - The power of public opinion, personality, and a mandate to achieve certain promises as a leader. Alternatively, the power to maintain an internal culture against outside influence.

Innovative - The power to think of and deliver new solutions, whether those be tools, processes, partnerships, or something else.

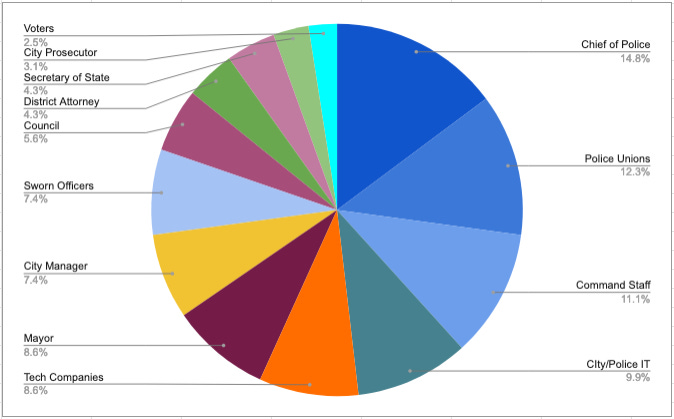

Finance, in purple, has two major components. Law and policy, in blue, has three. Culture and innovation are included to account for the strong personalities who often make change and lead from within, as elected officials and appointed operators, or from the outside as tech executives or changing voter concerns. I had hypothesized that because the Chief of Police is the most central and connected node in the power network, she would have a majority of the power. This was incorrect, to a degree. She had a plurality of power, but the agency as a coalition had a majority. This is easier to see here:

Two things were bothering me at this point. First, were the muscles weighted right? Was cultural power improperly boosted because it’s distributed, or discretionary power discounted because it’s concentrated? Should sums of columns be decided first, and split among actors? Second, I had 4 or 5 groups (depending on how IT is categorized) that were inside the agency - what was preventing the addition of more and more subgroups that would increase the Agency total or Government total or the Outsider total? I sought another opinion.

I walked through it with a California-based political consultant and former lobbyist, expecting a positive response with maybe a couple minor tweaks. His reaction was captured on camera, the footage of which is below.

“Cute model, Mitch. Yeah, it’s a decent formula, but it’s so static that it’s functionally useless.” Static. Cities are fascinating because of their dynamicism, which the matrix was flattening beyond recognition. Cities are all different, and so even if I nailed the picture for one particular city, it would be unusable for cities with slightly different structures or players. Cities also change over time, and the leverage that certain actors wield increases or decreases depending on what is most important - or more commonly, what is most urgent - for the city or agency to focus on. Who sets the agenda in a union negotiation, or budget setting, or policy creation? That is a better question than how much innovative influence does X or Y have on a scale of 0-5.

Let’s identify the new muscle types. Well, new isn’t the right word. Derivative might be better. Because of how unique most cities are, specific powers like in the earlier matrix are too prescriptive. We’re going up a level. A good analogy might be looking at skeletal muscle vs smooth muscle instead of bicep vs tricep. I see four types, with time as a dynamic fifth that makes them all relative:

Hiring and Firing - This power is the most formal, stable, and predictable. It involves the dynamics of one’s direct reports, whom one reports to, what work products one is accountable for, and how one is to be replaced.

Agenda Control - The power to have one’s preferred issues known and addressed first. Often gives the ability to frame them in a way conducive to the preferred result.

Pecuniary - The power to procure, impact, or spend (discretionary) funds above the floor of personnel costs.

Executive Enforcement - The power to have the last say, or oversee the ‘last mile.’ To subjectively execute or not execute one’s duty (e.g. a decision to not ticket jaywalking, or to not enforce purging policy)

Time - The god who fires us all, eventually. In the meantime, it makes the fluctuation of power among the above four dynamic, locale-specific, and interesting.

It’s taken some work, but here we are. This feels like a good place to leave it for now, and we’ll pick it up and apply it soon.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy this newsletter, please share it, forward it to your friends, or just sign up here. Happy Monday!

(Non-Work) Reading Recommendations

My Own Private Iceland by Kyle Chayka

Good Life by Anna Gát, a weirdly philosophical look at the Despacito music video

The Spy Who Drove Me by Julia Ioffe, a glimpse into paranoia/hilarity in the modern intelligence community

I Accidentally Uncovered a Nationwide Scam on AirBnB by Allie Conti